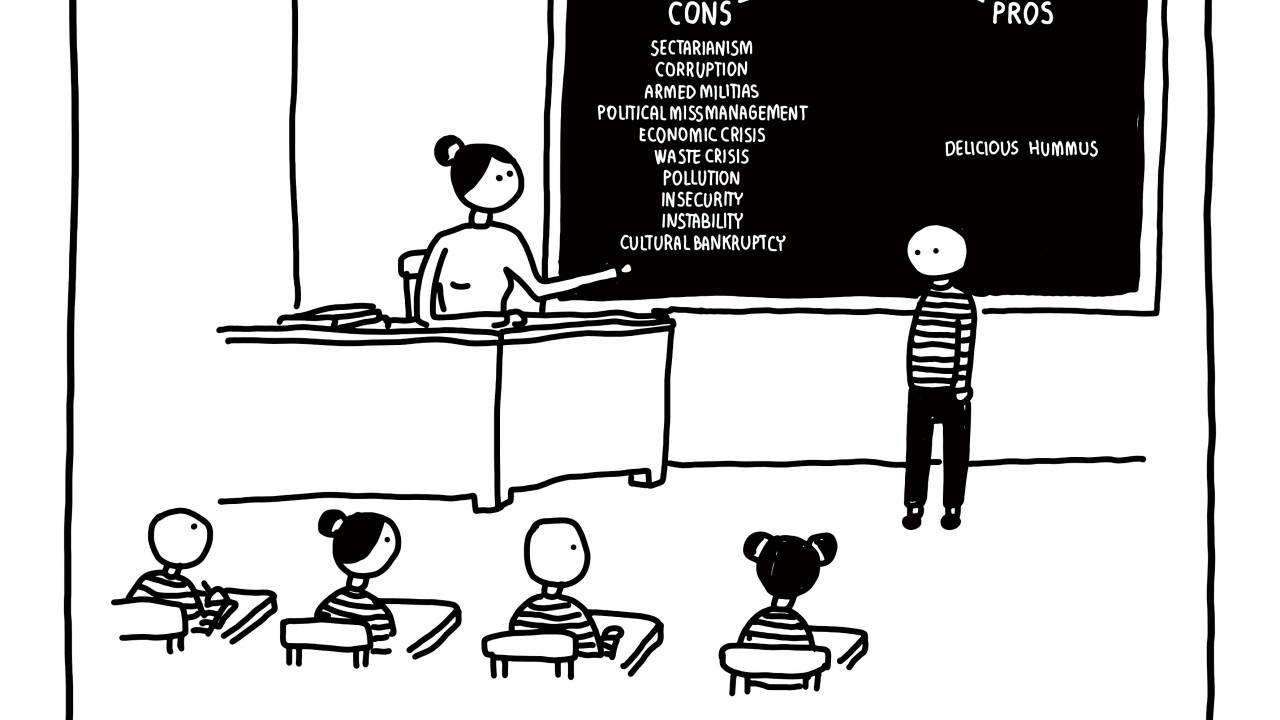

Caught between the dark waves of economic collapse and explosion, Lebanese artists struggle to stay afloat. Many have already chosen to leave.

On 4 August, at 18:07, negligence and corruption materialised into a monstrous blast, which took at least 200 lives, injured 5,000 and left 300,000 homeless. The explosion severely damaged Beirut’s residential and commercial quarters, known for their trendy restaurants, bars and cafés, as well as being a major hub for local artists, galleries, and cultural activities.

When Art Doesn’t Pay

This devastating event has crowned an exhausting and seemingly never-ending period of hardship for the people of Lebanon, who are currently enduring the country’s worst economic crisis since gaining independence in 1943. Hyperinflation, unemployment and extreme poverty amount to a veritable humanitarian disaster. One in five Lebanese families skip meals or even go without food for a whole day in order to survive. That is not to mention the ongoing political unrest since October 2019 and the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic.

This catastrophe has also had a terrible immediate effect on the artistic scene. Most artists have been out of work since the popular uprising, when suddenly many art venues closed their doors causing all commissions and paid jobs to dry up. Just keeping a roof over their heads has become a daily struggle for many artists.

When a space is damaged so too is the creativity that resides there

I count myself a proud member of these unfortunates. Apart from publishing political cartoons in the local French-language daily L’Orient Le Jour since 2012, I have mostly freelanced as a graphic designer to put food on my table. I was able to put my master’s degree to work developing brand identities for new businesses, or promotional materials for those looking to relaunch. My earnings in 2020 so far have been remarkably modest, namely, 15% of what I brought in last year. This situation has pushed me out of my comfort zone, leading me to do things that I had never dreamed of – like writing this article for example.

Artists have also been affected by the banking crisis and the unprecedented capital controls which have been imposed without any grounding in law. Anthony Sahyoun, a musician and sound engineer of one of Lebanon’s leading recording studios, Tunefork Studio, tells zenith: “Banks have tightened limits on all payments outside Lebanon, so we can’t pay the fees for our website. If we lose access to our websites, we risk losing our work portfolio and many of our clients.”

First to Crash, Last to Heal

In circumstances as dire as these, the cultural sector is the first to crash and the last to heal. The symptoms of this collapse can be traced by observing the deteriorating living conditions of local artists and cultural organisations. These have been compounded by August’s blast which wrought the most devastation on Gemmayze and Mar Mikhael, the neighbourhoods where many artists live and work.

When a space is damaged so too is the creativity that resides there, Nour Hifaoui: “My workspace has been severely affected, I tried going back there days after the explosion, but I couldn’t handle the weight of despair that occupied the room.” The illustrator and board member of Samandal (Salamander), a local platform dedicated to the art of comics, continues: “It was once my safe place and now it’s more like a nightmare. I’ve lost my sense of productivity, the hardest thing for me right now is to grab a pencil and draw.”

If you believe that suffering forges better art, then Beirut must have one of the world’s best artistic communities.

The culmination of stress stemming from last autumn’s protests, economic crisis, coronavirus, and the recent explosion has left many artists in a state of emotional limbo. “I had to leave Beirut and stay over at friends’ places to get over what had happened.” Sahyoun continues: “I couldn’t sleep alone. Part of the studio was shattered, but thankfully our sound equipment was not damaged. Many musicians, who have no other source of income, have lost their gear. And there’s no syndicate of musicians to provide support.”

As the initial shock subsides, some silver linings can be glimpsed. If you believe that suffering forges better art, then Beirut must have one of the world’s best artistic communities. The city’s artists have honed their abilities to actively process grief through their work. Such hardship has also bred solidarity. Sahyoun himself has helped launch an initiative called Beirut Musicians’ Fund together with fellow Lebanese musician and founder of Tunefork Studios, Fadi Tabbal. Having reached out to many musicians and producers working within the blast radius, the initiative has estimated that $48,000-worth of damage to musical equipment has been sustained. “Until now we’ve been able to secure $35,000 of the total amount,” says Sahyoun.

Beirut Musicians’ Fund is one of many artist-led fund-raising initiatives which have sprung up in the aftermath of the blast. Illustrators, painters, photographers and musicians among others have auctioned off their work to raise money for frontline organisations such as the Lebanese Red Cross and Impact Lebanon. “Art Relief for Beirut”, an Instagram-based art fundraiser founded by Lebanese artist Mohamad Kanaan, was able to raise $100,000 during the first week of the initiative, with people contributing from around the world.

Culture of Neglect

When asked if Samandal had received any state support, Nour Hifaoui laughs: “They didn’t even help with the clean-up. Do you really think they’re going to support artists? Ironically, UNESCO France checked on our organisation though.” The Lebanese authorities’ disregard for the cultural scene is hardly breaking news. The artistic sector has always depended on the goodwill of private donors, like banks, embassies and institutions.

As Hifaoui explains, turning to the Ministry of Culture is never an option: “We were organising a youth comic project, which tackled issues of social, personal and intimate nature. We reached out to the Ministry of Culture for financial support. They just told us to instead work on topics like patriotism, the army and independence.” The ministry’s lack of recognition for artists means that artists in Lebanon also don’t enjoy a real professional status in the eyes of both the public and the authorities.

Trying to predict the future at this point is akin to locating Cyprus from a second-floor Beirut balcony in the dead of night through the lens of a camera phone.

In the absence of state support, cultural institutions, museums and galleries often step in, but they too have endured their fair share of hardship in recent weeks. Ashkal Alwan, the Lebanese Association for Plastic Arts, was forced to discontinue its annual programme because the banks seized its funds before the blast. Theatre Gemmayze, Artlab, Art on 56th, 392rmeil392, and Galerie Tanit were just some of the artistic hotspots damaged by the explosion. Letitia Gallery in the neighbourhood of Hamra had to shut its doors following the death of its director, 29-year-old Gaya Fodoulian, in the explosion.

The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) and Al-Mawred Al-Thaqafy (Cultural Resource), bodies which award grants to individual artists and cultural organisations across the Arab world, have launched an international fundraising campaign to help nearly 40 groups and 150 individual artists get back on their feet. Each of the two groups has contributed $50,000, their goal is to raise $300,000. Given the scale of the damage, UNESCO estimates that $500 million are needed over the coming year to support heritage and the creative economy.

What Does the Future Hold for Us?

Trying to predict the future at this point is akin to locating Cyprus from a second-floor Beirut balcony in the dead of night through the lens of a camera phone. This uncertainty is causing many artists, especially those who are cosmopolitan and multilingual, to consider leaving Lebanon. Hifaoui is one of them: “I would leave today if I could. I don’t feel safe here anymore. I can’t live with the constant fear that something terrible is about to happen. I don’t really care about the destination, I just need to be in a place that is safe.”

As the artists who stay turn to more non-artistic ways of making ends meet, the creative output will undoubtedly shrink – and with it Lebanon will lose much of its appeal. Hemmed in between endless political, financial and cultural hurdles, life in Beirut is simply becoming unbearable. The city will of course endure – with perhaps fewer storytellers to tell its tale.

Bernard Hage, known under the pseudonym “The Art of Boo”, is an illustrator and political cartoonist currently based in Beirut, who publishes weekly in L’Orient Le Jour, a leading French-language newspaper in Lebanon. Bernard has been working on his German language skills since 2018 and is considering spending some time in Berlin soon.

The content published on the Lebanon Chronicles channel is supported by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS). The views expressed in these articles are those of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the KAS.