Amid months of nationwide protests, one Lebanese’s mission to weed out endemic corruption tells the story of a country at economic breaking point.

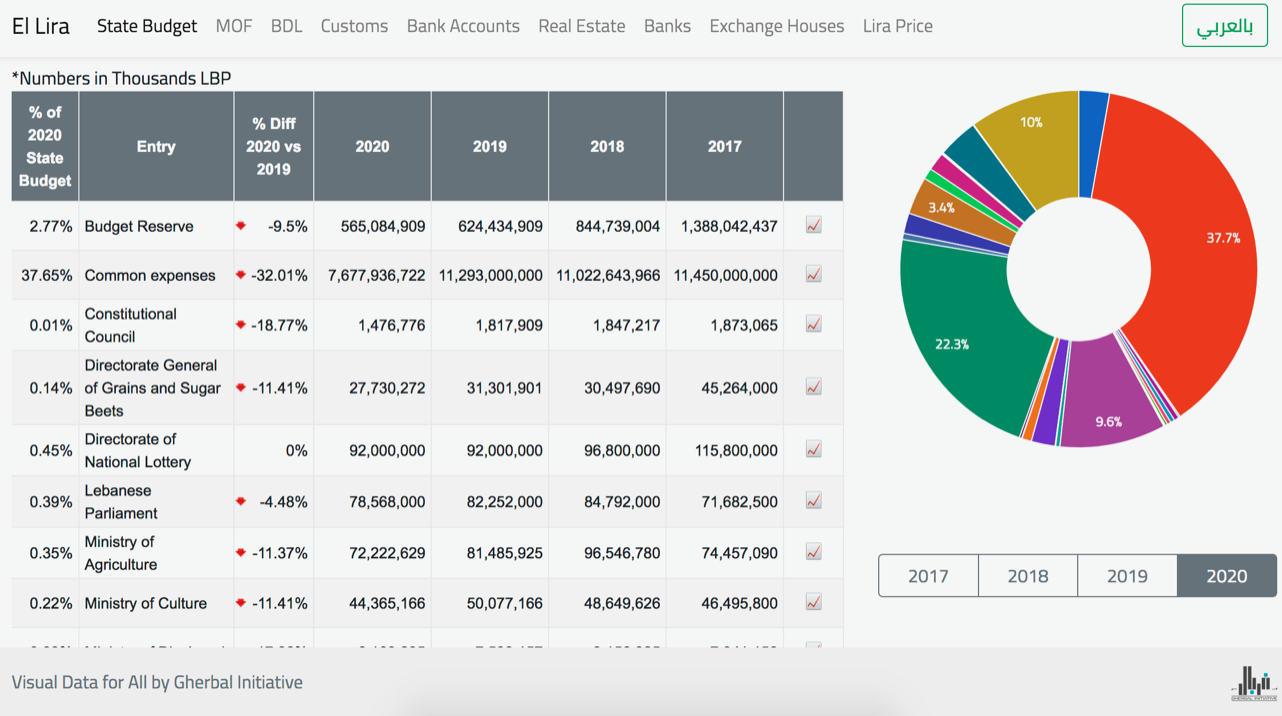

The 32-year-old Thebian, who has been active in Lebanese civil society for over a decade, founded the Gherbal Initiative in 2018. Since then the organisation has been relentlessly collecting budgetary data from different Lebanese state institutions which has until now been unavailable to the public. Thebian’s NGO transforms the data into eye-catching visuals which anybody can easily understand.

“Gherbal in English means sift,” the initiative’s founder explains. “We’ve been working on sifting through the data.”

The launch of their latest project, a website called El Lira, coincided with the dramatic devaluation of the formerly stable Lebanese pound. The site contains visualisations of data from the Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank and analysis of state budgets, as well as information regarding the currency rate on the black market, at exchange shops, and even in banks.

Lebanon is currently experiencing arguably its worst economic crisis in its history, and has just started negotiating with the International Monetary Fund for a bailout. Most Lebanese will point to a lack of transparency and the prevalence of corruption as key reasons for the country’s economic failure.

“I always wanted to have such a dossier,” Thebian told zenith: “Whenever politicians opens their mouths, I can just give them the numbers, the facts, the dates, and then I can tell them ‘ok, now defend yourself’.”

The Covid-19 restrictions imposed due to the Covid-19 outbreak are now in their third month in Lebanon, so Thebian finds himself alone in the initiative’s office - with only his cat for company. Having been born in 1988 and raised in the mountains of the Chouf, Thebian developed his interest in politics following the events of 7 May 2008, when Hezbollah’s 17-month-long political campaign against then-Prime Minister Fouad Siniora over his government’s anti-Syria stance turned violent resulting in armed clashes across the country.

It was a particularly politically charged period in recent Lebanese history, where all major parties were appealing to the country’s youth in particular for support. “That was a turning point for me,” Thebian says pensively. “I realised I wanted the system to change, because it was dysfunctional at all levels: socially, politically, economically – you name it.”

In March 2010, Thebian participated in his first protest, one pushing for a civil personal status law and civil marriage in Lebanon. It was a planned action near the Lebanese Parliament, where protestors dressed up as brides and grooms to stage civil marriages. “My friend who was organising asked me if I wanted to volunteer, and I said yes,” he said. Back then, Thebian believed that that supporting a cause that mattered to him was a harmless activity.

Thebian simply dressed up and volunteered, though what came next was a surprise.

“The parliament’s guards beat us up,” he said, still slightly somewhat taken aback. “This seemed crazy to me. I thought that I was just asking for basic human rights, and I’m being beaten up for it.”

It was not Thebian’s last run-in with the police. His arrest during the You Stink! Protests in 2015 became a viral moment. The protests broke out over the Lebanese government’s failure to solve the country’s escalating waste management crisis. He was daubing the concrete barriers covering in Lebanese flags in front of the Ministry of Interior with the movement’s eponymous slogan when security forces grabbed him and threw him in the back of a police jeep. All charges against Thebian were eventually dropped.

Many years of activism later, he feels that the battle for transparency and against corruption is the one that is most significant to him. “Everyone knows that there’s corruption in Lebanon. Many cases are reported in the media and some are referred to the judiciary,” Thebian explains while rolling another cigarette: “But we as the public don’t see the figures so we don’t really understand what’s going on.”

Corrupt and opaque practices are nothing new in Lebanon. “Corruption is rampant and is widespread across the highest offices and public institutions and all the way down to the lowest levels of everyday life,” Nadim El Kak, a researcher at the non-governmental think tank Lebanese Center for Policy Studies explained. “It has contributed in creating a culture where people have lost trust in the state.”

Lebanon’s ruling business magnates, ex-warlords, and elites rely on clientelist networks to fill in the gaps left by the lack of adequate state-provided social services. Whether it is a scholarship or a job, a medical expense or humanitarian aid, these parties are ready to support citizens in need in exchange for political loyalty.

This continues to this day, with different political parties now coordinating their own responses to the pandemic. These ruling parties also use employment in tax-funded state institutions to win political loyalty, seen as part of their notoriously wasteful spending of public funds and resources.

“There are conflicts of interest; they’re supposed to take care of the functioning of the institutions,” El Kak explains: “By undermining state institutions, they benefit at a party level by filling those gaps they’re creating by profiting off resources they get through those formal positions.”

Corruption is present in both private and public sectors. This includes the country’s main electricity provider, Electricité du Liban, which haemorrhages $2 billion in state funds annually, despite the continuation of regular power cuts, forcing households to pay a second bill to external generators. Lebanon has also squandered needless amounts of money on temporary waste management solutions since 2015, where the state has awarded private companies generous contracts, often owned by profit-hungry “cronies.”

Unsurprisingly, most Lebanese perceive their country as extremely corrupt. Lebanon ranks 137 out of 183 surveyed countries in Transparency International’s 2019 Corruption Perception Index.

Keeping track of these misappropriations of public funds became Thebian’s calling. He tells zenith that he continues to be amazed by the true scale of the mismanagement since launching the Gherbal Initiative. “Most spending is on salaries, bonuses, and benefits,” Thebian notes: “This is absurd for a state that is suffering from high levels of incompetency while people lack public services.”

Thebian added that there are cases of ministers signing off on two seemingly “contradictory” documents.

He nevertheless still believes that there are good people within these institutions and ruling parties who want to collaborate for the better of the country. And this motivates him to continue his work. “Those whose names you never hear of tend to be more cooperative,” he said, adding that they almost never speak to the press or are prominently featured in the media.

“Activism isn’t just going on television and screaming and demanding. Activism is wanting to change something,” Thebian explains: “Change wouldn’t happen except in two ways: either drastic change which could happen in a real revolution … and if there isn’t a real revolution then you have to be pragmatic and try to change things from within as long as you don’t change your principles.”

Lebanon has witnessed a mass uprising against the country’s ruling parties and banks on 17 October 2019 over the spiralling economic crisis. Though numbers have dwindled, protests and riots have sporadically broken out as the currency crisis continues to worsen.

The Access to Information Law

Thebian noticed an opportunity when Lebanon in 2017 passed the Access to Information Law, eight years after the draft law made its way to parliament. The law was passed with little buzz, but it eventually became the inspiration behind the Gherbal Initiative.

The law was a major legislative breakthrough as it allowed citizens to file information requests to different state or state-contracted institutions, who are responsible to designate a representative to respond to these requests. In theory, journalists, activists, researchers and concerned citizens can now have their questions answered that are often left ambiguous in press statements. This is considered a huge breakthrough, considering the transparency issues the country has faced. Prior to its implementation, the United Nations Development Programme described the law as a “gateway to fighting corruption.”

“When they passed the Access to Information Law in 2017, I thought maybe we should do something about it. But we really didn’t know what to do at the time,” Thebian says while trying to keep his cat off his desk.

This new tool was initially underused. But Thebian saw an opportunity to take things forward and began submitting access to information requests to all public administrations in Lebanon.

Soon after the law was passed, and before the Gherbal Initiative formally began its work, prominent civil society organisations, which filed requests early on, were surprised to find out that they received rejections. This included prominent civil society organisations like Legal Agenda, comprising lawyers and legal experts. They, alongside others, feared that passing the law would be nothing more than a publicity stunt by the government. By passing such a law the government would be able to flaunt their commitment to transparency and legal reform in public, while keeping things as they always had been behind the scenes.

Gherbal’s activists sent access to information requests to 133 of Lebanon’s 150 public administrations. Why only 133? “Some are non-functioning.” Only 34 of the 133 responded, and about half of the responses were refusals to share the data with Thebian and his colleagues.

“What I concluded with my colleagues after this was that the law will not be implemented if someone doesn’t care to check or monitor whether it’s applied or not,” he explains: “And we realised that there are both good and bad people in the administrations – some who will try to help you and want to share the information with you.”

But Thebian said he felt that the only way to pressure the authorities to enact important laws like the Access to Information Law is through public pressure.

“Passing the Access to Information Law did not happen without pressure, and it was passed in a way that nobody would hear much about it,” he says, explaining that the Gherbal Initiative wanted to increase the visibility of this important tool.

Over the past two years, the organisation has submitted over 400 information requests, and trained numerous journalists, activists, and other organisations to incorporate this tool into their work.

And it appears to have paid off. “We now have MPs attending our events,” Thebian says proudly, adding that he recently got off a call with the prime minister’s office.

Where does Lebanon go from here?

Lebanon has for years been promising international donors that it will pass and implement anti-corruption legislation. Its most recent and significant commitment so far came in April 2018 at the CEDRE conference in Paris, when the international community pledged $11.1 billion, mostly in loans, for development projects in exchange for economic and structural reforms. The Lebanese government has been scrambling ever since to unlock these loans from 50 donor states and organisations including the World Bank, EU states, the USA, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. These loans, designated for development projects, can help jumpstart its economy and improve its ailing infrastructure, including its ineffective electricity sector, under-utilised commercial ports, highways and sewage treatment plants.

Parliament passed a long-awaited anti-corruption law in late April, which mandates the formation of an anti-corruption commission. The law is imperfect to say the least, as it only tackles the public sector and the commission’s members are appointed rather than voted.

Once the committee is established, however, it would activate a long-awaited whistle-blower protection law, which Thebian says would be significant. These developments, while promising, represent just a tiny step forward.

“Let’s admit that there are a few reforms legislatively passed, but they are not implemented,” Thebian said.

And while he does not want the Gherbal Initiative to be a permanent plaster on the wounds of the Lebanese state – as he believes the state should be sharing their data publicly in the first place – he is adamant to continue with the pressure, pointing to piles of binders and folders of information in his office that have yet to be visualised.

His organisation has received praise and plaudits from journalists and policy researchers alike. “These initiatives are really important … this is a very long battle,” says El Kak: “But there are so many reforms that need to be undertaken and ‘small victories’ that need to be accomplished, so we need to have those alternatives that expose malpractices and play a role in pushing for these reform efforts.”

Lebanese lawmakers are currently debating a draft law over the independence of the judiciary. Activists fear that it may be diluted by the time it is voted on in parliament.

Despite the tenacity of Thebian and his colleagues at the Gherbal Initiative, they know that an independent judiciary is more crucial than ever to complement their efforts. After all, how else could people be held accountable?

“The pressure is now there, but this will all be in vain if you don’t have an independent judiciary system,” he says.

“As long as the judiciary system is not independent, there is no progress. As long as the political system is built on clientelism and sectarianism, we’re not going to get anywhere.”

It appears Assaad Thebian has work to do.

Kareem Chehayeb is a Beirut-based freelance journalist and analyst for independent media organisation The Public Source. His work has featured in The Washington Post, Foreign Policy, Al Jazeera English, Middle East Eye, and The New Humanitarian, among others.

The content published on the Lebanon Chronicles channel is supported by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS). The views expressed in these articles are those of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the KAS.