By the time a judge acquitted Adam Ramer* of drug-related charges, the 28-year-old had already spent just over 21 months in pre-trial detention. More than half of the country’s inmates suffer a similar fate. How can this be?

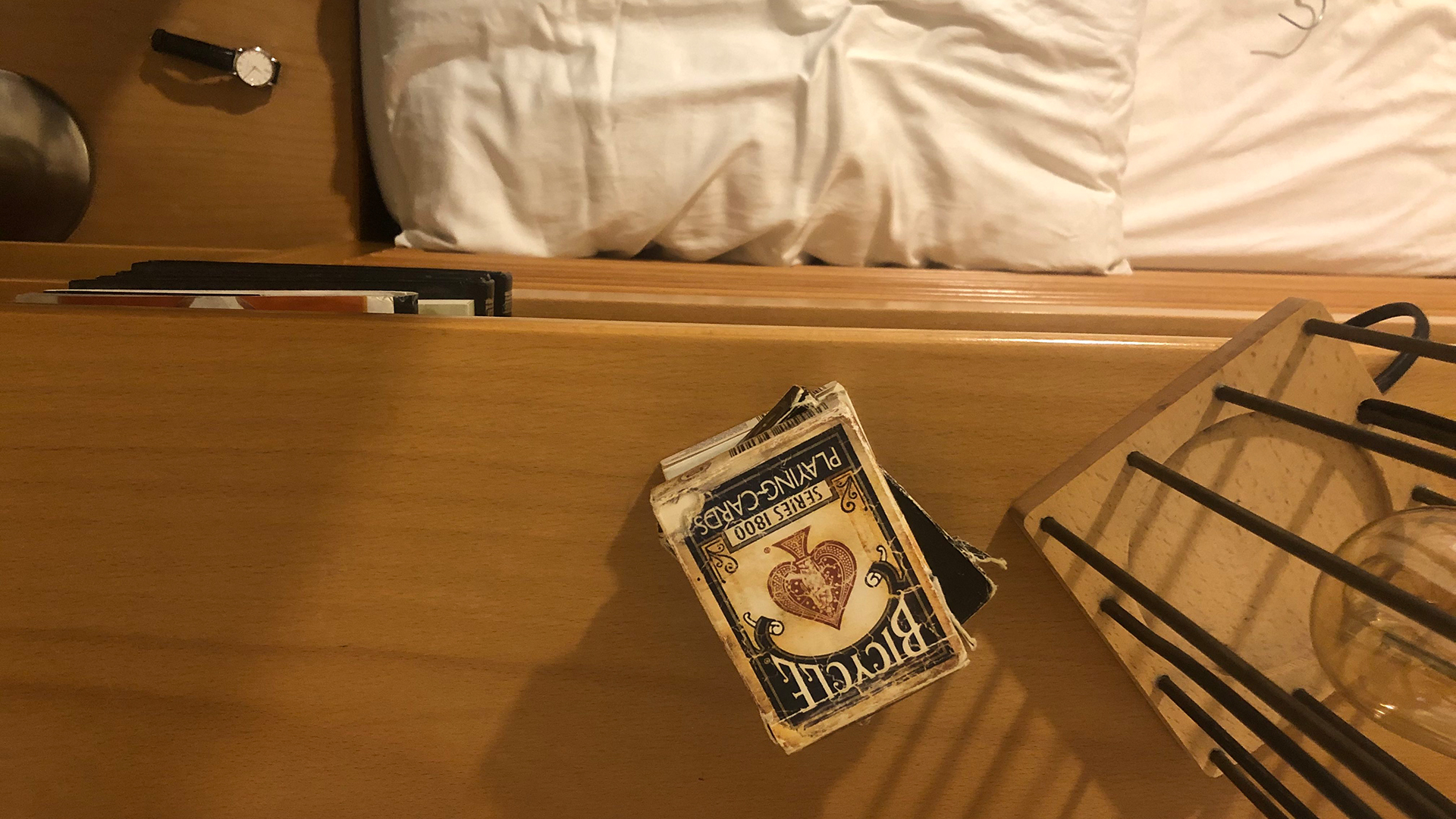

Lockdown has left Adam feeling he is once again behind bars. When he is not preoccupied with his latest freelance assignment, he is likely to be found shooting off emails to potential employers or procrastinating with the help of funny YouTube videos. Other than his case files, three worn-out packs of playing cards stacked next to his desk are the only reminder of his two-year-stretch in Lebanon’s prison system.

In 2014, Adam Ramer, not his real name, was arrested and charged with trafficking and manufacturing psychedelic drugs, both serious crimes in Lebanon’s justice system. He spent the next couple of years detained in three different prisons. Three weeks in both Beirut’s Hobeiche police station and Tripoli’s Qubbah prison, followed by 20 months in Aley’s minimum-security detention centre in Mount Lebanon. He was eventually released on bail in 2016 only to be incarcerated once again during his trial in October 2019 where he was finally acquitted. To those unfamiliar with Lebanon Adam’s story may seem somewhat outlandish, however, within the country itself it is pretty much the norm.

A report by Legal Agenda, a Lebanese NGO that conducts research on socio-legal matters, estimated that in the first half of 2017 54% of the country’s inmates were in pre-trial detention while presumed innocent. The organisation has dubbed the practice “punishment before conviction.”

Adam sat in prison for months on end waiting for his day in court. As he recounts the story, his voice still betrays a lingering grudge. His sinewy figure is completely clad in black; two ornate rings adorn his finely manicured right hand. To stay safe in prison, he had to bribe the self-appointed guardians of the inmate population known as shewishe, a nickname borrowed from an outdated military rank.

When Adam finally stood trial, two years after he was released on bail and a full five years after he was initially arrested, the judge declared him innocent on most of the original counts. Adam was, however, found guilty of drug use and possession. “It was a minor offense that I confessed to straight away,” he says: “Most people don’t get prison time for it, so my lawyer advised me to plead guilty.”

Most Lebanese lawyers would also consider Adam’s misdemeanor to be rather inconsequential. Adam explains that the court used this conviction to justify his detainment, when he raised the question of compensation after he was acquitted. The report by Legal Agenda suggests that time spent behind bars may negatively influence final verdicts: “Judgments will tend to reach a conviction rather than an acquittal in order to legitimise the prolonged pre-trial detention.”

Adam’s descent through Lebanon’s prison system

For safety concerns Adam prefers not to get into the specifics of his case. What he could say was that the police had intercepted packages of psychedelic drugs which they believed were meant for him. According to Adam, a drug dealer tried to frame him and his friends, after one of them rejected his marriage proposal. Adam’s degree in health sciences counted against him too when the police interpreted his research as proof of ‘intent’ to manufacture drugs.

And so began his painful ordeal with the Lebanese criminal justice system. After spending three weeks in the Hobeiche police station detention centre in Beirut, Adam was transferred to Tripoli’s Qubbah prison, a former stable. Inmates slept on the floor unless they could afford to bribe the shewishe for a mattress, which Adam did. The prison was managed entirely by the prisoners themselves, most of whom were also awaiting trial on charges of homicide and terrorism. Adam recalls: “At night the shewishe’s gang would amuse themselves by shocking sleeping inmates with electricity or sexually abusing the Syrian prisoners.”

Three weeks later, his lawyer - who charged a $50,000 retainer that Adam’s parents collected from his relatives - got him transferred to Aley’s minimum detention center in Mount Lebanon where Adam would spend 20 months rehearsing his defense for the day of his trial. “The first six months are the most difficult,” Adam says: “Then you get sucked into the routine.” He spent his days playing cards and gambling over packs of cigarettes. He read Arabic movie subtitles to illiterate inmates and made friends by sharing food parcels his parents sent him. Fellow inmates died in front of his eyes, succumbing to heart attacks or seizures, convulsing as everybody watched. “The guards weren’t allowed to touch them without authorisation.”

After 20 months, a sympathetic judge reviewed Adam’s case and decided there was no justification to keep him detained. She released him on bail.

Diala Haidar, Amnesty International's Lebanon and Jordan campaigner, told zenith that Lebanon had signed the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights which guaranteed a detainee’s right to appear quickly in front of the court. “This law didn’t come out of nowhere,” Haidar says: “It exists to protect the detainee from torture and mistreatment, and to consecrate his right to a lawyer. Lebanese laws should be modified accordingly.”

Arbitrary detention is not only a blatant human rights violation, but also the main reason for prison overcrowding. In August 2018 the prison population across Lebanon’s 23 detention centres numbered at least 6,600, in facilities designed to hold only 4,800 inmates.

A violent welcome

The first blow had come just moments after the police seized Adam from his parents’ house in Beirut and bundled him into their van. “On the way to the police station, they asked me if I had smoked up. When I said no, one of them elbowed me in the gut.”

Though a judge eventually cleared Adam, the police were convinced of his guilt from the very beginning. At the precinct Adam was deprived of a lawyer but cooperated by answering all questions. The interviewing officer nevertheless repeatedly paused the questioning to punch him in the face or throw him across the room.

A report published by the UN Committee Against Torture in 2014, published a few months after Adam’s arrest, concluded that torture in Lebanon was “routinely used by the armed forces and law enforcement agencies for the purpose of investigation, for securing confessions to be used in criminal proceedings and, in some cases, for punishing acts that the victim is believed to have committed.”

After being questioned, Adam was held in a communal cell, which was no larger than a small trailer. Many of the 23 men crammed in there bore the severe bruising of sustained interrogations. A hole in the ground served as a toilet. “The room’s only ventilation was an opening in a wall and a fan on the other side of a louvered door,” Adam explains: "We’d fight over who could take out the trash, just to breathe freely for a few seconds.”

According to the study by Legal Agenda, the law allows prosecutors to hold detainees in custody for a maximum of four days before charging them, as a safeguard against unnecessary detentions. In practice the real number is closer to six and can take up to 19. Detainees are also supposed to appear in front of a judge within 24 hours of being charged. The judge decides whether the detainee should get released on bail or kept in detention. In reality this usually takes around five days due to court understaffing.

Caught up in a broken system

To prevent arbitrary arrests the law also requires investigative judges to specify the reason for an individual’s detainment in writing. This was not done in Adam’s case, nor is it when most others are arrested. The shortage of judges, as well as the absence of oversight and disciplinary measures, means that these violations often go unpunished.

Detainees, like Adam, can spend days, months or years in pretrial detention because a judge is too busy to assess their cases. Obstacles in communication between different judicial bodies and the security apparatuses that are holding prisoners are also to blame. Political tensions and government gridlocks, in a country rife with them, often translate into extra prison time for those without the proper connections to move their case up the broken bureaucratic ladder.

Adam’s case was particularly difficult because his charges were drug related: “Everyone will tell you that a murder charge is easier than a drug charge in Lebanon” he told zenith.

This assumption has some truth to it. The law that sets a cap on pretrial detentions makes an exception for both homicide and drug crimes. This means that those who are accused of drug or homicide crimes could remain in pretrial detention indefinitely, and that would be perfectly legal. Article 108 of the Lebanese code of criminal procedure sets the maximum period allowed for pretrial detentions at two months for misdemeanors, and six months for felonies, both terms can only be renewed once. These safeguards, however, do not apply to offences relating to drugs, homicide, and terrorism.

“The law considers them serious crimes because they are dangerous to the fabric of society,” Mohammad Mrad, the president of the Tripoli Bar Association, explains to zenith: “But that does not mean that those accused of drug dealing or murder cannot be released. The Tripoli Bar Association has always raised questions about the narrow interpretations of Article 108. Pretrial detention should be the exception not the rule.”

Since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 Mrad says his team has joined forces with the new president of the Beirut Bar Association, the Higher Judicial Council, the Ministry of Justice and the public prosecutor’s office to release those who are currently awaiting trial in prison. So far 500 out of the 1500 pretrial detainees in northern prisons have been released. Mrad expects another 250 releases in his districts during the coming months.

Trapped in a sectarian standoff

Lebanon's system of sectarian power-sharing means all 18 sects participate to varying degrees in governing the country. Decisions from nationwide electoral laws to small-scale appointments of public officials must preserve the delicate balance struck by this accord. This system’s drawbacks translate into delays in judge appointments, postponement of court dates, unresponsive security apparatuses, and decades of stagnation regarding legal and procedural reforms.

“No one would tell me why my requests for release were getting refused,” Adam says: “The judge just writes ‘rejected’, without any explanation.”

Two controversial bills that would grant general amnesty to thousands of prisoners are currently caught in a parliamentary tug-of-war. Critics denounce the bills as another clientelistic ploy by the ruling class to exacerbate sectarian tensions and to allow their associates to go unpunished for their crimes. They believe that Sunni and Shia parliamentary blocs mainly support these bills because prisoner’s families comprise a huge percentage of these blocs’ voting base. One critic told zenith that though prisoners deserved release, political leaders should not be allowed to exploit justice for political campaign promises, while also wiping their own slates clean.

Behind prison walls sectarian tensions are also strong. Qubbah prison, located in the predominantly Sunni city of Tripoli, is no different. “ISIS graffiti decorated the walls,” Adam says: “And drug-fuelled inmates can suddenly decide to attack someone just because he belonged to a different sect, for example.” Because he was a Sunni, Adam was mostly left alone. He only ran into some trouble when he became friendly with another inmate transferred from Roumieh prison which was a facility located a 15-minute-drive north of Beirut with a predominantly Shia population. The ongoing vendetta between Qubbahand Roumieh in many ways mirrors the sectarian tensions that have governed Lebanon for decades.

The prison in Aley, a majority Druze region of Mount Lebanon, had two holding cells - one run by the Druze and another by the Shi’a. Adam was put in the Druze cell, and a $200 bribe to his young shewishe earned him safety, a mattress, and a glass of vodka for his first night.

Two years later: release, trial, lockdown

“What’s an Uber?” Adam asked his friends after his release on bail in 2016, having missed out on the latest technological developments while inside. Back home he was reminded of the pain and the financial cost he had inflicted on his family. Nightmares kept Adam awake, but his problems were not confined to his dreams.

His trial still loomed. He could not leave Lebanon, and any job interview meant justifying a mysterious two-year gap on his otherwise stellar resume. Adam’s luck changed in 2019, however, when he was given a job in a company’s marketing division. It was 10 October that same year when he finally walked into the courthouse; his 28th birthday. Having defended himself in court, Adam was to be placed under arrest for one more week to await the verdict.

One last week in prison soon became two. The day before his court date, and just a few hundred meters away from Adam’s prison cell in Beirut’s Adlieh detention centre, angry protesters blocked the highway. The worsening economic conditions triggered demonstrations across the country demanding, among other things, the government’s resignation, an independent judiciary and the end of sectarianism.

“I appreciated the thawra’s [revolution] demands, but nothing was worth spending another week inside that hellhole.” As Adam laughs his otherwise hard features soften. On 25 October Adam’s mother picked him up. A judge had found him innocent. He was going home.

Months later, Adam sits in a country under lockdown, new riots erupted across Lebanon’s overcrowded prisons over fears of the coronavirus. State prosecutor Ghassan Ouweidat ordered judges to hold off on pretrial detentions unless “absolutely necessary”. Despite contacting officials working in two different legal authorities in Lebanon, nobody was prepared to talk to zenith.

Lawyers from Beirut and Tripoli’s bar associations are receiving daily calls from prisoners asking for their paperwork to be processed and their release granted.

When asked about what stays with him of his two years in prison, Adam pulls out his set of cards. He asks me to pick one and place it in the middle of the deck. “I kept watching this guy in Aley because he wouldn’t teach me his tricks. Eventually, I learned them on my own.” When he reshuffles the deck, the card magically reappears at the top: “How else was I gonna spend all that time?”

* The name has been changed to protect the protagonist’s identity. The author has full knowledge of his identity and the facts of his case.

Jonathan Dagher is a journalist and producer at the Lebanese independent online media platform Megaphone News. In summer 2019 he participated in RSF Germany’s Berlin Scholarship Programme.

The content published on the Lebanon Chronicles channel is supported by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS). The views expressed in these articles are those of the respective authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the KAS.